© Garden Cottage Nursery, 2022

Why Did They

Change The Name?!

Taxonomy

When a plant species is first described by a botanist in a learned journal, monograph or flora it is a description based upon a

specimen the botanist believes to be typical for the species. This “type” specimen is kept dried and pressed in a herbarium and

clearly marked as the type for that species against which all other examples in the future must be compared.

The first species of a genus to be described is taken as also being the “type” for the genus so any plant with pretensions to being

included in the type’s genus must share enough characters to justify sharing the generic name.

As we said earlier Linnaeus gave us a binomial system for naming plants by genus and species. He identified and classified plants

by sexual characters, essentially counting the number of stamens and carpels a plant had and grouping together those with similar

numbers and shapes.

Without a more accurate way of gauging plants relationships to each other “gross morphological” based plant classification

continued along like this for another 200 or so years.

In the 1950s James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, and Rosalind Franklin identified the DNA helix, the punch card that

programmes cell creation for all known life on Earth.

In 2000 the Human Genome Project finished it’s first draft and since then computer and DNA sequencing technologies have raced

forward so that it is now comparatively cheap and quick to sequence the genes of plants.

Genes mutate at a fairly steady rate over generations so with lots of clever thinking and number crunching it is possible to roughly

gauge how long ago certain allele arose and with enough current samples across the range you can work back down the branches

of the family tree plants to see where groups diverged. Studying organisms evolutionary history is known as Phylogenetics.

Phylogenetic studies of plants over the last 15 or so years have thrown up all manner of surprises as to the true relationships

between plants compared to the assumed relationship we grew up with.

A number of old plant families and genera have been shown to be not actually directly related or to have included interlopers from

other branches.

Most recent name changes amongst well known garden plants have come about through phylogenetic studies that have revealed

what were single genera to be polyphyletic.

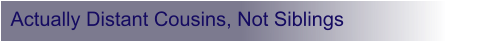

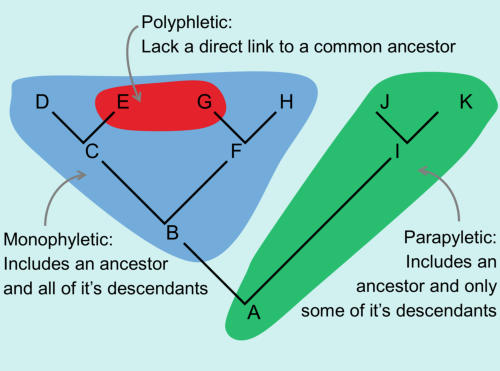

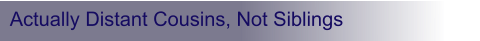

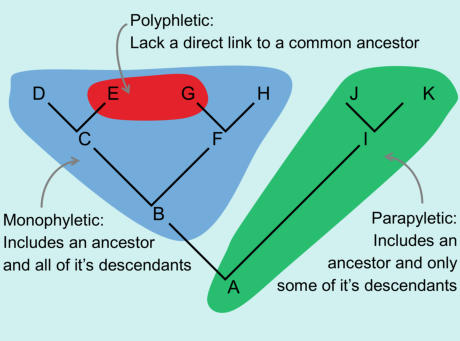

A Polyphyl is made up of groups of species from different branches or twigs of the tree of life, sometimes even with already

separately named genera in between. They have certain shared traits but these are the result of convergent evolution

(independently developing the same traits) or reversion rather than a common ancestor. Genera or families should be

monophyletic, all emerging from a common locus.

Some plant name changes occur because diligent botanists have spotted that plants described as a different species or in different

genera are not distinct enough, or even at all, to justify a separate generic or specific name: Schizostylis coccinea was sunk back in

to Hesperantha coccinea.

Sometimes a single or group of related species are deemed distinct enough from the other plants in the genus to deserve a genus

of their own: Lithospermum diffusum to Lithodora diffusa.

Other changes occur when a plant became widely known by one name which was actually published after the plant had already

been validly described under a different name: Primula littoniana to Primula viallii.

On occasion plants have become widely known by incorrectly spelled names: Buddleia to Buddleja.

Changes to plant names usually take quite a while to bed-in and reach general acceptance amongst botanical institutions, so by the

time they come to the attention of gardeners they will probably have been thoroughly tested and checked.

Quite a few recent name changes that affect gardeners happened because a genus of plants was shown by phylogenetics to only

be a subset, or scattered amongst members of a second broader genus and were therefore not thought to deserve to have their

own generic epithet and were ‘sunk’ into the broader genus.

Much of the recent revisions have been collected into the works of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (AGP) who published 4 major

papers between 1998 and 2016 that reshaped the understanding of the tree of life for flowering plants.

Phylogony showed that Cimicifuga (left) had it’s species scattered amongst the

family tree of Actaea (below), so all Cimicifuga were renamed to be Actaea.

Going in the opposite direction:

The popular perennial known as ‘Dutchman’s Breeches’, Dicentra spectablis (above) was found to be on it’s own separate

branch of the poppy family from the other Dicentra (below) so was given a new genus to become Lamprocapnos spectablis.

Asteraceae, the daisy family has compound ‘flowers’ made of composite inflorescens of often hundreds of small flowers gathered

together. Their small size and the similarity between species of the individual flowers have historically made discerning their

relationships to to each other difficult based on gross morphological characters.

Unsurprisingly Asteraceae is full of very large polyphylectic genera in need of sorting out, unfortunately for gardeners many of these

jumbled genera include popular garden plants.

Aster amellus is the type species for both the genus Aster and the family Asteraceae, as such it’s name is pretty much set in

taxonomical stone. The genus Aster is polyphylectic and just about all the varieties we grow in our gardens as Aster come separate

branches of the Asteraceae tree to Aster, so their names should be changed, including:

Eurybia divaricata

Galatella linosyris

Galatella sedifolia

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum

Symphyotrichum novi-belgii

Symphyotrichum tradescantii

Aster diplostephioides

Many of the Eurasian species of Aster remain unchanged, a fair few of which are commonly cultivated.

Aster x frikartii 'Mönch'

© Garden Cottage Nursery, 2021

Why Did They Change The

Name?!

Taxonomy

When a plant species is first described by a botanist in a

learned journal, monograph or flora it is a description based

upon a specimen the botanist believes to be typical for the

species. This “type” specimen is kept dried and pressed in a

herbarium and clearly marked as the type for that species

against which all other examples in the future must be

compared.

The first species of a genus to be described is taken as also

being the “type” for the genus so any plant with pretensions to

being included in the type’s genus must share enough

characters to justify sharing the generic name.

As we said earlier Linnaeus gave us a binomial system for

naming plants by genus and species. He identified and

classified plants by sexual characters, essentially counting the

number of stamens and carpels a plant had and grouping

together those with similar numbers and shapes.

Without a more accurate way of gauging plants relationships to

each other “gross morphological” based plant classification

continued along like this for another 200 or so years.

In the 1950s James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins,

and Rosalind Franklin identified the DNA helix, the punch card

that programmes cell creation for all known life on Earth.

In 2000 the Human Genome Project finished it’s first draft and

since then computer and DNA sequencing technologies have

raced forward so that it is now comparatively cheap and quick to

sequence the genes of plants.

Genes mutate at a fairly steady rate over generations so with

lots of clever thinking and number crunching it is possible to

roughly gauge how long ago certain allele arose and with

enough current samples across the range you can work back

down the branches of the family tree plants to see where groups

diverged. Studying organisms evolutionary history is known as

Phylogenetics.

Phylogenetic studies of plants over the last 15 or so years have

thrown up all manner of surprises as to the true relationships

between plants compared to the assumed relationship we grew

up with.

A number of old plant families and genera have been shown to

be not actually directly related or to have included interlopers

from other branches.

Most recent name changes amongst well known garden plants

have come about through phylogenetic studies that have

revealed what were single genera to be polyphyletic.

A Polyphyl is made up of groups of species from different

branches or twigs of the tree of life, sometimes even with

already separately named genera in between. They have

certain shared traits but these are the result of convergent

evolution (independently developing the same traits) or

reversion rather than a common ancestor. Genera or families

should be monophyletic, all emerging from a common locus.

Some plant name changes occur because diligent botanists

have spotted that plants described as a different species or in

different genera are not distinct enough, or even at all, to justify

a separate generic or specific name: Schizostylis coccinea was

sunk back in to Hesperantha coccinea.

Sometimes a single or group of related species are deemed

distinct enough from the other plants in the genus to deserve a

genus of their own: Lithospermum diffusum to Lithodora diffusa.

Other changes occur when a plant became widely known by

one name which was actually published after the plant had

already been validly described under a different name: Primula

littoniana to Primula viallii.

On occasion plants have become widely known by incorrectly

spelled names: Buddleia to Buddleja.

Changes to plant names usually take quite a while to bed-in and

reach general acceptance amongst botanical institutions, so by

the time they come to the attention of gardeners they will

probably have been thoroughly tested and checked.

Quite a few recent name changes that affect gardeners

happened because a genus of plants was shown by

phylogenetics to only be a subset, or scattered amongst

members of a second broader genus and were therefore not

thought to deserve to have their own generic epithet and were

‘sunk’ into the broader genus.

Much of the recent revisions have been collected into the works

of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (AGP) who published 4

major papers between 1998 and 2016 that reshaped the

understanding of the tree of life for flowering plants.

Phylogony showed that

Cimicifuga (left) had it’s

species scattered amongst

the family tree of Actaea

(below), so all Cimicifuga

were renamed to be Actaea.

Going in the opposite direction:

The popular perennial known as ‘Dutchman’s Breeches’,

Dicentra spectablis (above) was found to be on it’s own

separate branch of the poppy family from the other Dicentra

(below) so was given a new genus to become Lamprocapnos

spectablis.

Asteraceae, the daisy family has compound ‘flowers’ made of

composite inflorescens of often hundreds of small flowers

gathered together. Their small size and the similarity between

species of the individual flowers have historically made

discerning their relationships to to each other difficult based on

gross morphological characters.

Unsurprisingly Asteraceae is full of very large polyphylectic

genera in need of sorting out, unfortunately for gardeners many

of these jumbled genera include popular garden plants.

Aster amellus is the type species for both the genus Aster and

the family Asteraceae, as such it’s name is pretty much set in

taxonomical stone. The genus Aster is polyphylectic and just

about all the varieties we grow in our gardens as Aster come

separate branches of the Asteraceae tree to Aster, so their

names should be changed, including:

Eurybia divaricata

Galatella linosyris

Galatella sedifolia

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum

Symphyotrichum novi-belgii

Symphyotrichum tradescantii

Aster diplostephioides

Many of the Eurasian species of Aster remain unchanged, a fair

few of which are commonly cultivated.